I’d wanted to write last night about Donald Trump’s ever-changing position on mandatory background checks for gun sales, and the pathetic way in which he publicly grovels at the feet of the NRA, but, when I saw that one of my favorite films, Preston Sturges’s delightfully thoughtful 1941 screwball comedy Sullivan’s Travels, was going to be on television, I decided to take a little time off. And, apparently, I’m still under its spell. Here it is 24 hours later, and I’m still making my way down Sullivan’s Travels-related rabbit holes. Last night, I was trying to find verification that Charlie Chaplin had stopped Sturges from using footage of his Little Tramp character in the film’s well-known church scene. And, today, I’ve decided to spend my time trying to figure out the etymology of the word “beasel,” which is uttered by the protagonist’s butler about half-way through the film. Here’s that exchange from the film’s script… For those of you familiar with the film, this exchange takes place as Burrows (Robert Greig), the butler, drops off his employer, film director John L. Sullivan (Joel McCrea), and his companion (Veronica Lake), at a Los Angeles hobo camp so that they might be able to hop a train east.

SULLIVAN TO THE GIRL (WHO IS DRESSED LIKE A BOY): You look about as much like a boy as Mae West.

THE GIRL: All right, they’ll think I’m your frail.

BURROWS: I believe it’s called a “beazel,” miss, if memory serves.

[I didn’t know this until I started doing some research, but “frail,” when used as a noun, is — or at least was — a slang term for a slight girl or woman.]

OK, so it’s not something I’m likely to get to the bottom of right now, but here’s what I’ve found thus far.

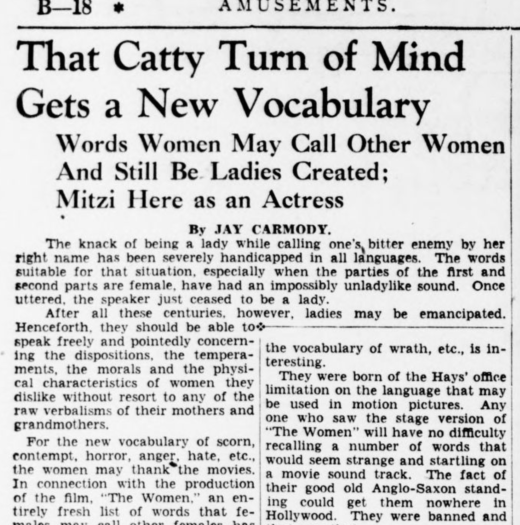

While the word “beazel” is used in Sullivan’s Travels, most of the discussion around the term seems to be centered around its use by Rosalind Russell two years earlier, in George Cukor’s brilliant 1939 film, The Women. And, in that case, most people seem to think it was used because censors wouldn’t allow either “bitch” or “floozie” to be used, and the producers had to find an alternative. [I haven’t been able to confirm this, but I’ve seen it mentioned that The Women’s published screenplay spells the word “beezle”.] Here, with more on this, is a clip from the July 31, 1939 edition of the Washington, D.C. Evening Star.

And, perhaps because of this article, and that line about how “there was nothing for the studio to do but to coin an entirely new set of words,” a good number of people still seem to think the word was essentially pulled from the ether by the screenplay’s author. The truth, however, seems to be that the word significantly predated The Women, having first been used a quarter of a century earlier, during the era of the flapper.

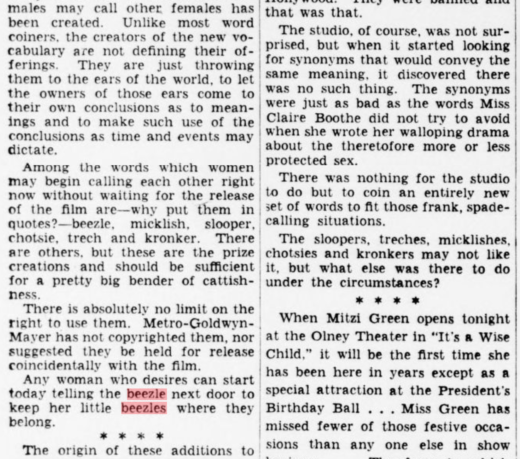

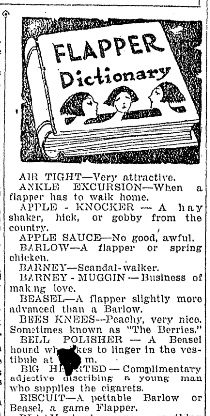

To the right, you’ll see a piece that ran in the Logansport Pharos-Tribune, in Logansport, Indiana, on April 25, 1922. As you’ll notice, the word not only pre-dated The Women by decades, but it’s defined in such a way as make sense in the context of both films… A beazel, as you can read here, is essentially a more experienced flapper. And, by flapper, of course, we mean, a young, fashionable, independent, modern woman, who, according the dictionary, is “intent on enjoying herself and flouting conventional standards of behavior.” [If you’ll recall, American women had just won the right to vote in 1920, with the passage fo the 19th Amendment, so the theme of the independent woman had pretty much permeated popular culture.]

To the right, you’ll see a piece that ran in the Logansport Pharos-Tribune, in Logansport, Indiana, on April 25, 1922. As you’ll notice, the word not only pre-dated The Women by decades, but it’s defined in such a way as make sense in the context of both films… A beazel, as you can read here, is essentially a more experienced flapper. And, by flapper, of course, we mean, a young, fashionable, independent, modern woman, who, according the dictionary, is “intent on enjoying herself and flouting conventional standards of behavior.” [If you’ll recall, American women had just won the right to vote in 1920, with the passage fo the 19th Amendment, so the theme of the independent woman had pretty much permeated popular culture.]

So, Veronica Lake, in Sullivan’s Travels, dresses like a boy in hopes of avoiding suspicion while hopping freight trains with her new-found director friend, gets told that her disguise isn’t working, responds by pretty much saying, “So, they’ll think I’m an innocent, non-sexual, androgynous girl,” only to essentially be told by the butler, “No, it’s pretty clear that you’re an independent, sexual, modern woman who knows exactly what she’s doing.” At least that’s my reading of things. [So, she’s not as naive as a barlow, and not as sexually experienced as a biscuit, but somewhere in between.] If you disagree, let me know.

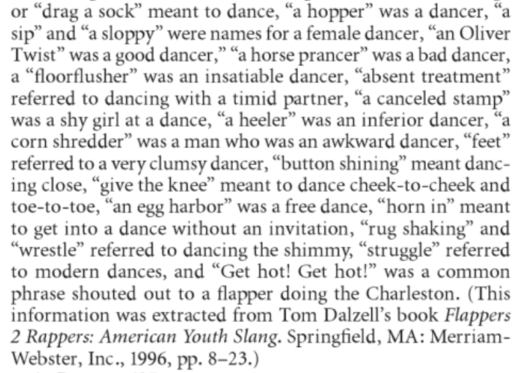

And, now, I can’t stop reading about flapper slang. The following comes from page 235 of the book, The Wicked Waltz and Other Scandalous Dances: Outrage at Couple Dancing in the 19th and Early 20th Centuries. As you can see, the definition of beazel remains fairly consistent with what was presented above from 1922.

Or, if you don’t want to talk about beazels, we can talk about common sense gun control, you pettable crumb-gobblers.